Queen and Lover are Re-united at the V&A’s

Latest Show

Yet portraits could also speak the language of love. Reunited on the walls of the V&A are two figures forever bound by their historic passion for each other. I am talking of course about Queen Elizabeth I and her most beloved and adored Courtier- Lord Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester.

Having seen and studied these paintings separately for so long, it seems rather odd to force them together in the naturally contrived space of the exhibition. It becomes hard to imagine the real people that lived and breathed under those restrictive court costumes and behind those frozen faces. Yet the life of opulence and luxury that the Royal Court acted out during these times lives on in the objects they left behind. The gifts traded across nations speak volumes: about the style of the time, about impressive native craftsmanship, and about the cultural, political and even personal messages that they carried with them.

The same can be said for the exquisite jewels,

miniatures and gems on display here, especially the Drake Jewel, which is undoubtedly

one of the nation’s most precious treasures.

By A. Crossland

The Victoria and Albert's new exhibition ‘Treasures of the Royal Courts: Tudors, Stuarts and Russian Tsars’ chronicles centuries of Royal extravagance

in gifts, gifts which often travelled thousands of miles in order to impress foreign

dignitaries in far away lands. From Ivan the Terrible, through the courts of

Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, and ending with the Stuart monarchs, this

exhibition displays some 150 exhibits from both Russian and English Royal

courts. On exclusive loan from the Moscow Kremlin Museum is

an extensive collection of disgustingly ornate silverware given to the Russian

Tsars by English monarchs. The skill displayed in the execution of these colossal

wine jugs, platters and serving dishes fills the red walled rooms of the V&A

with a shining, glittering light. Surely no modern machinery could ever make

works of art such as these.

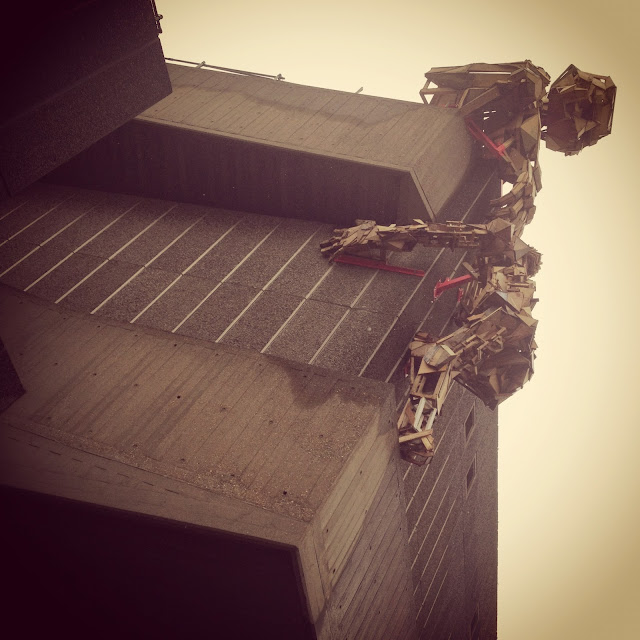

The glamour of the Elizabethan joust is displayed in the detailed designs for the head to toe armour worn by such men as Sir Christopher Hatton, in honour of their most beloved Virgin Queen.

|

| A beautifully executed drawing of armour made for Sir Christopher Hatton. Unfortunately the original does not survive. Image: Royal Armouries |

Henry VIII’s armour is also on display, catching in the eye in a different way, as it confirms the King’s rather excessive lifestyle; and waistband.

Portraits in this exhibition highlight how the painted form was used in a conscious way to confirm the sitters’ power status. In the days before any formal propaganda or public representation existed, portraits were the language of social power. Works copied and engraved were shipped across the continent to inspire and impress foreign counterparts. This dialogue of works helped to inspire artists and spread artistic development across the world.

|

| Queen Elizabeth I, Image: Philip Mould |

Portraits in this exhibition highlight how the painted form was used in a conscious way to confirm the sitters’ power status. In the days before any formal propaganda or public representation existed, portraits were the language of social power. Works copied and engraved were shipped across the continent to inspire and impress foreign counterparts. This dialogue of works helped to inspire artists and spread artistic development across the world.

Yet portraits could also speak the language of love. Reunited on the walls of the V&A are two figures forever bound by their historic passion for each other. I am talking of course about Queen Elizabeth I and her most beloved and adored Courtier- Lord Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester.

|

| Robert Dudley, 1st Earl Leceister. The two heraldic devices inform the viewer of Dudley's fine pedigree. The dog symbolises fidelity and loyalty. |

Having seen and studied these paintings separately for so long, it seems rather odd to force them together in the naturally contrived space of the exhibition. It becomes hard to imagine the real people that lived and breathed under those restrictive court costumes and behind those frozen faces. Yet the life of opulence and luxury that the Royal Court acted out during these times lives on in the objects they left behind. The gifts traded across nations speak volumes: about the style of the time, about impressive native craftsmanship, and about the cultural, political and even personal messages that they carried with them.

|

| The Drake Jewel. Image: elizabethan-portraits.com |

My only regret about the execution of this

exhibition is the inclusion of rather rudimentary and simply worded

descriptions to the objects. The V&A could have gone a lot further in

discussing the symbolic nature of many of the elements in the paintings, jewels

and other objects on display. The symbolic language of Court life during these

times is surely one of the most fascinating elements of this historical period.

To leave these signs unaddressed means that the underlying message of these diplomatic gifts is lost to a society that can no longer read the signs themselves.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/treasures-of-the-royal-courts/about_the_exhibition/

'Treasures of the Royal Courts: Tudors, Stuarts and Russian Tsars' runs from 9th March-14th July 2013.

TICKET PRICES:

General admission: £14

Student: £7

Art Fund: £4.70

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/treasures-of-the-royal-courts/about_the_exhibition/

'Treasures of the Royal Courts: Tudors, Stuarts and Russian Tsars' runs from 9th March-14th July 2013.

TICKET PRICES:

General admission: £14

Student: £7

Art Fund: £4.70